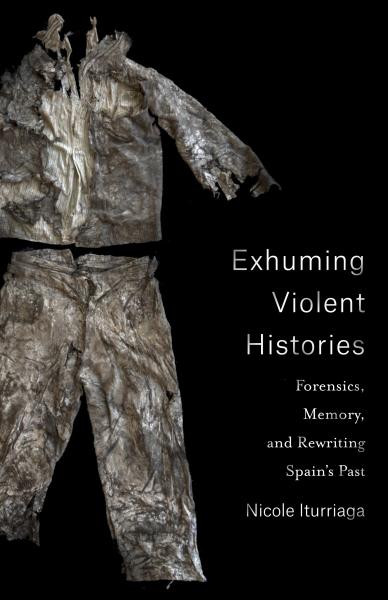

Nicole Iturriaga’s first book, “Exhuming Violent Histories,” demonstrates how activists use new methods for human rights. Photo by Han Parker

New book highlights how science and technology intersect with human rights

Nicole Iturriaga’s just-released book, “Exhuming Violent Histories: Forensics, Memory, and Rewriting Spain’s Past,” highlights how Spanish human rights activists have turned to science and technology to keep the memory of state terror alive.

By excavating mass graves, exhuming remains, and employing forensic analysis and DNA testing, Spanish human rights activists seek to provide direct evidence of repression and break through the silence about dictator Francisco Franco’s atrocities that persisted well into Spain’s transition to democracy.

By excavating mass graves, exhuming remains, and employing forensic analysis and DNA testing, Spanish human rights activists seek to provide direct evidence of repression and break through the silence about dictator Francisco Franco’s atrocities that persisted well into Spain’s transition to democracy.

Iturriaga, assistant professor of criminology, law and society, offers an ethnographic examination of how Spanish human rights activists use forensic methods to challenge dominant histories, reshape collective memory and create new forms of transitional justice. She argues that by grounding their claims in science, activists can present themselves as credible and impartial, helping them intervene in fraught public disputes about the remembrance of the past. The perceived legitimacy and authenticity of scientific techniques allows their users to contest the state’s historical claims and offer new narratives of violence in pursuit of long-delayed justice.

Iturriaga draws on interviews with technicians and forensics experts and provides a detailed case study of Spain’s best-known forensic human rights organization, the Association for the Recovery of Historical Memory. She also considers how the tools and tactics used in Spain can be adopted by human rights and civil society groups pursuing transitional justice in other parts of the world.

“Exhuming Violent Histories,” published by Columbia University Press, Iturriaga notes, explores how human rights activists use forensic interventions to challenge dominant narratives of violence, thereby contesting the state’s claims over historical memory, notably of the highly problematic authoritarian Francoist period. It draws from 15 months (2015-2017) of participant observation with the Association for the Recovery of Historical Memory, 230 interviews with activist and non-activist Spaniards, and a historical study of secondary literature of the global forensics-based human rights social movement emerging from post-authoritarian Argentina.

More explicitly, the book argues that by grounding their claims in science, human rights activists present themselves as credible and impartial rather than as partisan and biased activists. “In other words, they draw on science, international protocols, and tropes of modernity to depoliticize their account of state terror,” Iturriaga explains.

“Exhuming Violent Histories” reveals that the activists, using what Iturriaga calls a “depoliticized approach,” can meaningfully shape transitional justice efforts by challenging traditional beliefs about “warranted” state terror and collective memories of violence through the deployment of international law and advocacy networks.

“This global movement’s sovereignty and legitimacy, has risen — in many cases — above that of the nation-state, creating a new venue and vision for human rights justice,” Iturriaga says, adding that her book “adds to a growing interdisciplinary field of memory studies by analyzing the mechanisms through which social actors rewrite collective memories of state terror and demand transitional justice; particularly meaningful during the current and global reckonings of histories of violence.”

The following is an excerpt from “Exhuming Violent Histories”:

In August 2015, I found myself alongside the technical team of the Association for the Recovery of Historical Memory (ARMH) working in the summer Andalusian heat to painstakingly uncover the mass grave of four victims of forced disappearance. The victims, two workers of the local village and their wives, had been brutally executed by deserted road at the hands of rebel fighters in September 1936, two months after the beginning of the Spanish Civil War. The almost forty-year dictatorship that followed (1939-1975) mandated that victims like these be remembered only with disdain and disgust, as they were pronounced as traitorous Marxists deserving of their deaths, their families denied the right to mourn or perform important death rites. The democratic transition (1975-1978) that followed the death of the dictator, Francisco Franco, also institutionalized a sanitized silence about the past preserving the Francoist structure of victors and losers, all in the name of maintaining political stability. It wasn’t until the new millennia that the global social movement of forensics-based human rights arrived in Spain and gave rise to Spanish human rights workers breaking both the repressive silence of the past and the ground to tell the true story of Spain’s violent history.

Back at the grave, one of the women—Rosa—was revealed to have a red earring resting on her cranium; all four victims still had their wedding rings. Since this was my second exhumation ever, I was given the task of excavating—or removing the topsoil from—Rosa’s feet, so that they would be completely uncovered. Due to the dryness of southern Spain, both the skeletal remains and the soles of the victims’ shoes were well conserved (see fig. 0.1). As I was focusing on breaking or ruining anything in the dig—in spite of the crash course training I received as an ARMH volunteer, ultimately, I am a sociology, not an archeologist!—some locals from the village came by to see the work. They whispered that Rosa had been eight months pregnant at the time of her death. I kept working, all the while thinking about what they had said. Later, while uncovering her soles, it dawned on me that Rosa and I wore the same exact show size. I even held my show nears to check. I then quickly scaled myself alongside her and discovered that we had the same build and stature. I was looking at myself in a mass grave.

The forensic analysis of Rosa’s remains confirmed that she was around twenty to twenty-four years old at the time of death. She died, alongside her husband and his parents, from a bullet wound to the head and was buried facedown; what remained of her clothes was one red earring, a traditional Spanish hair comb, the soles of her shoes, and her wedding ring. As only one earring was found, it was thought she must have suffered some sort of violence where the other was knocked off. Small bone fragments thought to be fetal bones are still being analyzed by volunteer forensic anthropologists. In 2018, her village reburied her and the rest of the victims in a small ceremony. They honored them as the grandparents of democracy, who deserved to be buried and remembered with the deepest reverence.

Exhuming Violent Histories is an ethnographic exploration of how social actors, like the ARMH described above, are using a variety of tools and tactics to fight for control over collective memories of state terror and to reconceptualize what obtaining justice for that terror means. Specifically, it looks at the global forensics-based human rights social movement through a case-study analysis of Spanish human rights workers and their use of both global and local tactics (performance, pedagogy, framing, transnational activist networks) to legitimize their movement’s reframed narrative of Spain’s past violence and achieve new forms of post transitional justice. The book’s central questions are focused on unpacking how much rights workers find authenticity through science, among other tactics, when engaging in memory wars over violent pasts: How do science and technology intersect human rights regimes and collective memory work, and how does this, in turn, impact justice models and efforts?

Succinctly, this book argues that human rights workers use forensic interventions—such as exhumations—to challenge dominant histories of violence, thereby contesting the state’s control over historical memory. These workers, by grounding their claims in science, present themselves as credible and impartial rather than partisan and biased. In other words, they draw on tropes of modernity to de-politicize their account of state terror. As such, human rights workers, using what I call a “depoliticized approach,” can meaningfully change dominant narratives of violence—such as how we remember the history of Rosa, her family, and why they were murdered—as well as shape new models of justice in cases of long-ago violence and continued impunity.